When Code is Data

You may find yourself itching to write a new programming language, or at least learn why someone might want to write a new programming language. Perhaps it looks like JavaScript. Well, JavaScript is a complicated language. If I were to give you the following code:

for (let i = 1; i <= 100; i++) {

if (i % 15 === 0) {

console.log("FizzBuzz")

} else if (i % 3 === 0) {

console.log("Fizz")

} else if (i % 5 === 0) {

console.log("Buzz")

} else {

console.log(i)

}

}

How would you... run this? You'd probably save it as google-interview.js and run node google-interview.js. Fair. But what if you didn't have node? What might a program look like that could interpret this code?

interpret("for (let i = 1; i <= 100 ...")

// 1, 2, Fizz, 4, Buzz, ...

Enter the wild world of interpreters. Perhaps we want to just eval this code and get an answer, or maybe we want to compile it into *waves hands* something that we'll run on another machine, or on the same machine but much more quickly. Let's not get ahead of ourselves, and just talk about interpreting our code.

First we need to convince ourselves (and our interpret function, usually called eval) what a for loop is. It's defined as having the following:

- an initializer (a variable

iset to1) - a test condition (

i <= 100) - an update to run on each iteration (

i++) - and finally, a "body" of code to run on each iteration (the if statement and all the stuff inside of that)

You and I could sit here for an hour and work through some code that could interpret these! It might look like the following:

function runForLoop(obj) {

// Helper functions left as an incredibly boring and

// tedious exercise for the reader

let currVal = buildInit(obj.init);

let test = buildTest(obj.test);

while (test(currVal)) {

runBody(obj.body);

currVal = runUpdate(currVal, obj.update);

}

}

runForLoop({

init: {

type: "Assignment",

name: "i",

value: {

type: "Number",

value: 1,

},

},

test: {

type: "BinaryExpression",

op: "<=",

left: {

type: "Variable",

name: "i"

},

right: {

type: "Number",

value: 10,

},

},

...

})

// 1, 2, Fizz, 4, Buzz, ...

It's got everything we need! The init, the test, and... the other stuff. The details of which we'll gradually add color too, but for now recognize that we're capable of turning some object that looks for-loop-y into some output. You're welcome to run through such an exercise if you so wish.

But something looks different here. How did we get from for (let i = 1; i <= 100 ... to that well-organized (and written on the fly so please excuse any abnormalities and typos) JSON object? Welcome to the world of parsing, an art that humans have gotten pretty good at over the last 2,400 years.

Parsing is the act of taking an input string (our source code for (let i = 1; ...) { ... }) and turning it into a data structure ({ init: { ... }, test: { ... }, update: { ... }, ... } - this is commonly referred to as an Abstract Syntax Tree) that we can easily iterate over to ✨ compute ✨ a result.

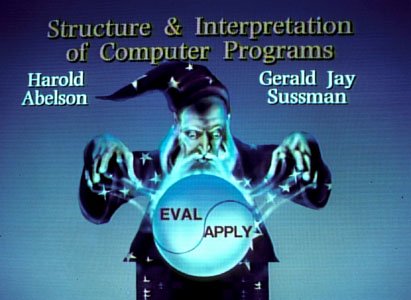

For JavaScript, we would use something like Acorn or @babel/parser. But what if we could skip it all? What if we could iterate directly over our source code, instead of needing to translate it into a tree? Allow me to put on my wizard hat and robe.

The Lisp family of programming languages uses a syntax that is full of parentheses and looks quite foreign to those familiar with C-style syntax (think: curly braces, semicolons on each line, fn(1, 2) function calls). Here's some code written in Racket.

(+ 5 10)

; => 15

(define (factorial n)

(cond ((= n 0) 1)

(else

(\* n (factorial (- n 1))))))

(factorial 10)

; => 3628800

But it's not all that complicated. Just about everything is an S-expression (a list of lists) and the syntax can be roughly (very roughly) summarized to the following:

- Literals like

1and"hello"look like you'd expect from any other language - Function calls are written as

(fn a b c ...)instead offn(a, b, c, ...) - Several "special forms" exist like

(if test a b),(cond ((condition-1) ...) (else ...)), and(define (fn arg1 arg2) ...)that behave different from ordinary function calls - Lists are written using

(list 1 2 3)or via the act of "quoting" where we put a single apostrophe in front:'(1 2 3)- Oh and they can be nested

'(1 2 (3 4) 5)

- Oh and they can be nested

An arithmetic expression, followed by a quoted arithmetic expression:

(+ 5 (\* 3 4))

; => 17

'(+ 5 (\* 3 4))

; => '(+ 5 (\* 3 4))

Here's where it gets interesting.

(first '(+ 5 (\* 3 4)))

; => '+

(second '(+ 5 (\* 3 4)))

; => 5

(third '(+ 5 (\* 3 4)))

; => '(\* 3 4)

(first (third '(+ 5 (\* 3 4))))

; => '\*

Remember our for statement from above? for (let i = 1; i < 100; ...) { ... }. When we wanted to interpret it, we first needed to parse it into a fancy JSON object that listed out the various parts before we could get a result. Let's try it for our little math expression here using AST Explorer.

5 + (3 \* 4)

{

"type": "ExpressionStatement",

"expression": {

"type": "BinaryExpression",

"left": {

"type": "Literal",

"value": 5,

},

"operator": "+",

"right": {

"type": "BinaryExpression",

"left": {

"type": "Literal",

"value": 3,

},

"operator": "\*",

"right": {

"type": "Literal",

"value": 4,

}

}

}

}

To get the values we need to start computing, we can poke around this as follows:

ast.expression.operator

// => '+'

ast.expression.left

// => { type: 'Literal', value: 5 }

ast.expression.right

// => {

// type: 'BinaryExpression',

// left: { type: 'Literal', value: 3 },

// operator: '\*',

// right: { type: 'Literal', value: 4 }

// }

ast.expression.right.operator

// => '\*'

For Lisp? Our source code is an S-expression.

'(+ 5 (\* 3 4))

And we can happily dance around it to get the fields we need to start computing.

(first (third '(+ 5 (\* 3 4))))

; => '\*

(second (third '(+ 5 (\* 3 4))))

; => 3

There is no parsing step. There is no AST Explorer because our AST is right in front of us.

This property of the Lisp family of languages is called "code as data" or - if you want to impress your coworkers - Homoiconicity. It has many interesting consequences, from expressive macro systems and syntax extensions to self-modifying code, but for this purposes of this short essay we'll stick to interpreters.

Let's say our arithmetic expression (+ 5 (\* 3 4)) - which, is valid Lisp syntax - is part of a small language with the following:

- Numbers are written literally, that is

'5is just 5. - We can add exactly two expressions with

(+ a b) - We can multiply exactly two expressions with

(\* a b)

Without much code-golfing we can achieve this in 8 lines of Racket code.

(define (eval math-exp)

(cond ((number? math-exp) math-exp)

((eq? '+ (first math-exp))

(+ (eval (second math-exp))

(eval (third math-exp))))

((eq? '\* (first math-exp))

(\* (eval (second math-exp))

(eval (third math-exp))))))

And for some tests:

(eval '42)

; => 42

(eval '(+ 4 5))

; => 9

(eval '(+ 5 (\* 3 4)))

; => 17

(+ 5 (\* 3 4))

; => 17

No parsing, no translating, just some quoted source code and a couple of firsts and eq?s. Why so simple? Because the code is just data.

One side effect of this is that extending our language is pretty simple, just some additions to eval. Let's try this out by adding a fancy if>= expression. We want it to be of the special form (if>= math-exp positive negative) which evaluates math-exp and runs positive if the result is greater than or equal to 0, and negative otherwise.

(define (eval math-exp)

(cond ((number? math-exp) math-exp)

((eq? '+ (first math-exp))

(+ (eval (second math-exp))

(eval (third math-exp))))

((eq? '\* (first math-exp))

(\* (eval (second math-exp))

(eval (third math-exp))))

; ✨

((eq? 'if>= (first math-exp))

(if (>= (eval (second math-exp)) 0)

(eval (third math-exp))

(eval (fourth math-exp))))))

And we see that with four extra lines to eval and nothing more, we get a cute if>= form that interacts nicely with everything else in the language.

(eval '(if>= (+ 3 4) 100 -9999))

; => 100

(eval '(if>= (+ -300 4) 100 -9999))

; => -9999

(eval '(+ 5 (if>= 0 100 -100)))

; => 105

To reiterate: (if>= 0 100 -100) may appear to be different from (\* 100 200) or (+ 3 4) but it's still just an S-expression and we've gotten pretty good at jumping around S-expressions to get what we need. We can continue tacking on new forms and operators onto eval (starting with / and continuing all the way to cond). What might an eval look like that can... eval its own source code?

I hope these examples change the way you look at programming languages and the syntax they are built upon. There are endless paths to continue learning about "code as data" and how it appears in different programming languages to different advantages.

Until then, enjoy learning more about programming languages, and be sure know to let me know what you find.

Thanks for reading